Published December 24, 2021

People broke out in rages on airplanes; some had to be duct-taped to their seats. On December 11, there were terrible tornadoes. After they passed, Bowling Green, Kentucky looked like Berlin in 1945. Carjacking and mass looting by gangs in hoodies became fashionable in the cities. Then Omicron came on strong, and the masks returned, and with them, the murderous looks that people give you in supermarkets when you’re not wearing one. Anthony Fauci was everywhere, and the president of the United States, a wintry old man in pipestem trousers, predicted “a winter of severe illness and death” for the unvaccinated.

‘Tis the season to be jolly.

Then a trivial thing happened that depressed me, I suppose, more than the public catastrophes: I drove toward an outlet mall on the way to finish Christmas shopping. The road squeezed from three lanes to two and a young woman in a Santa-red Honda Civic cut me off, passing on the right, and as she went by, she swiveled her head and glared at me, looking into my eyes, her face distorted with hatred and rage. I read her lips. She gave me the finger.

These things add up. It didn’t feel a lot like Christmas. I couldn’t sleep. I listened to recordings of Scottish laments at 3 a.m. (Jean Redpath singing, “Awa’ wi’ Canada’s muddy creeks and Canada’s fields o’ pine’/ This land o’ wheat’s a goodly land, but ach, it is nae mine!”) and read the Book of Job. When I get depressed, I try to figure out the Book of Job. I moved on to Ecclesiastes (“For all his days are sorrows, and his travail grief; yea, his heart taketh not rest in the night. This is also vanity”) and the Book of Lamentations.

I listened to Jacqueline Du Pre’s performance of Elgar’s dolorous Cello Concerto, which he wrote in 1919, just at the end of the Great War—a melancholy piece in the deepest registers of sadness and loss. Du Pre’s cello, a woozy, emotional instrument, sways, almost davening, in an ambivalence of suffering and reverence. Elgar said, around the time that he wrote the concerto, “Everything good and nice and clean and fresh and sweet is far away, never to return.”

That was how I was feeling toward the end of 2021. I felt, as many do, the strangeness, the alienation, as if we had crossed over into a different country: “This land, it is nae mine!”

Such estrangement (we are not ourselves) has become a theme on all political sides—a psychology of exile even in one’s own country. It is possible to be a stranger in time as well as in place: by the rivers of Babylon, where we sat down, and then we wept, when we remembered Zion.

I remembered meeting Jacqueline Du Pre in 1965 at the Plaza Hotel in New York, when she was a lovely prodigy, 20 years old and newly famous, a brilliant young cellist, and I was a young magazine writer, come to interview her. She was a burst of sunshine, blonde and giddy—innocently amazed by her own genius. She married Daniel Barenboim. A few years later, multiple sclerosis seized her, and soon she could no longer play the cello. She died at 42. So much magnificent music went unplayed. My sister Christina, a dancer, was also a beautiful woman who died, too young, of multiple sclerosis. Du Pre reminded me of Tina.

Around St. Lucy’s day, December 13 (“It is the year’s midnight, and it is the day’s,” wrote John Donne), we tried to buy a Christmas tree in town but were amazed to find that they were all sold out, so my wife went up into the woods and found a big branch of a white pine that had fallen in a windstorm; she dragged it down to the house and planted it in a pot of rocks and water against one wall of the living room, where it stands now, adorned with a galaxy of small, clear, white lights—a sort of feathering, Japanese, espalier effect: eccentric for a Christmas tree, but beautiful.

Christmas speaks of new life, eternity touching history in the sweetest way: God comes to us in the person of a baby—the synecdoche of the Incarnation. Christmas is the first step on the path to Calvary, of course—and thence, in the Christian scheme of things, to Redemption. Ad astra, per aspera: you reach heaven by a hard road. Christmas speaks above all of hope.

There’s also hope’s big brother, courage.

Oddly enough, in this bizarre year of politics and pandemic, the final words of John Kennedy’s inaugural address came drifting back to me: “Let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own.”

Kennedy considered courage to be the most important of all virtues. Hope works best when fortified by courage. When we undertake the hard work of courage (wrestling with time and our own mortality, fumbling in the dark, in the shadow of death), the labor is truly our own. That’s what Kennedy meant. The test of courage is whether it can be summoned up even after hope is gone.

What I come to Christmas this year seeking—what I pray for in the middle of the night when I am keeping monk’s hours—is strength and courage, mostly: for myself, for all of us. I pray for faith, which is even stronger than courage.

Being male, and old and wistful now—grumpy and archaic—I also wish there were a higher standard at work in the world, a kind of chivalry, a knightly, principled fortitudo. Long ago, this was called manliness. But the mice got at it and ruined the word.

There is so much unclean politics at the heart of things. The Gospel of Luke speaks of “peace, good will toward men,” but I have rarely seen such ill will—everywhere—as now. Politics has become a carnival of hatred and lies. Politics corrupts, just as incompetence disables and stupidity sabotages and loneliness terrifies and hatred kills. None of those can rise to the challenge of tragedy.

But courage can. Faith can.

Forgive me. It’s a shame to waste the happiest moment on the calendar in regret and half-pagan, metaphysical sulking. Christmas teaches God’s love, and human gratitude for it—and joy, if you can manage that transcendent thing. I will close up the Book of Lamentations and go downstairs to spend the day with people I love.

Love others. Try to make them happy. That is Christmas.

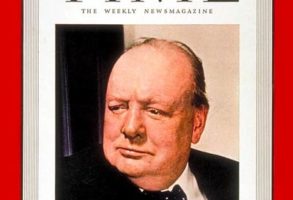

Lance Morrow, a contributing editor of City Journal and the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, was an essayist at Time for many years. His latest book is God and Mammon: Chronicles of American Money.

Lance Morrow is the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His work focuses on the moral and ethical dimensions of public events, including developments in regard to freedom of speech, freedom of thought, and political correctness on American campuses, with a view to the future consequences of such suppressions.