Published May 18, 2016

George Weigel's weekly column The Catholic Difference

If Catholics in the United States are going to be healers of our wounded culture, we’re going to have to learn to see the world through lenses ground by biblical faith. That form of depth perception only comes from an immersion in the Bible itself. So spending ten or fifteen minutes a day with the word of God is a must for the evangelical Catholic of the twenty-first century.

Biblical preaching that breaks open the text so that we can see the world, and ourselves, aright is another 21st-century Catholic imperative.

There is far too little biblically-based catechetical preaching—at which the Fathers of the Church in the first millennium excelled—today. The Church still learns from their ancient homilies in the Liturgy of the Hours, but the kind of expository preaching the Fathers did is rarely heard at either Sunday or weekday Masses. It must be, though, if the Church’s people are to be equipped to convert and heal contemporary culture. For the first step in that healing process is to penetrate the fog, to see ourselves for who we are, and to understand our situation for what it is.

How might biblical preaching help us do that?

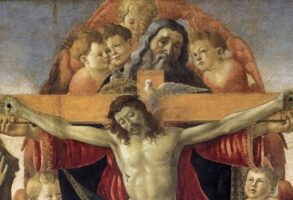

Take the recent Solemnity of the Ascension as an example. The essential truth of the Ascension is that it marked the moment in salvation history at which humanity—glorified humanity, to be sure, but humanity nonetheless—was incorporated into the thrice-holy God. The God of the Bible is God-with-us, Emmanuel. But, with the Ascension and Christ’s glorification “at the right hand of the Majesty on high” (Hebrews 1:3), humanity is “with God.” If the Incarnation, Christ’s coming in the flesh, teaches us that God is not distant from us, and if the Passion teaches us that God is “with us” even in suffering and death, then the Ascension teaches us that one like us is now “with God,” and indeed in God. Which means that humanity is capable of being sanctified, even divinized.

Eastern Christian theology calls this theosis, “divinization,” and it’s a hard concept for many western Christians to grasp. Yet here is what St. Basil the Great, one of the Cappadocian Fathers of the Church, teaches about the sending of the Holy Spirit, promised in Acts 1:8 at the Ascension: “Through the Spirit we acquire a likeness to God; indeed we attain what is beyond our most sublime aspirations—we become God.” What can that possibly mean?

It means that, through the gift of salvation, we are being sanctified: we are being drawn into the very life of God, who is the source of all holiness. And it means that our final destiny is not oblivion, but communion within the light and love of the Trinity. Why? Because the glorified Christ, present in his transfigured humanity to the first disciples in the Upper Room, on the Emmaus Road, and by the Sea of Galilee, has gone before us and is now “within” the Godhead, where he wishes his own to be, too.

Wonderful, you say. But what does that have to do with healing 21st-century culture?

Everything.

At the root of today’s culture of happy-go-lucky hedonism, which inevitably leads to debonair nihilism, is a profound deprecation of the human: a colossal put-down that tells us that we’re just congealed star dust, a cosmic accident—so why not enjoy what you can, as soon as you can, however you like, before oblivion? Why take your humanity seriously—including that part of your humanity by which you are constituted as male or female? You can change whatever you like; it’s all plastic and it’s all meaningless, because the only meaning of our humanity is the meaning we choose for it.

Christian faith offers a far nobler vision of the human condition than this dumbed-down self-absorption. Where do we find that nobler humanity exemplified? In the Ascension, and the incorporation of Christ’s human nature into the mutual love of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And where the Master has gone, the disciples are empowered by grace to follow.

That’s what should have been preached on the Solemnity of the Ascension. That’s the kind of preaching we need, day after day and Sunday after Sunday.

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington, D.C.’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies.