Published November 30, 2022

There are a lot of reasons why family formation—marriage and fertility—has seen a long downward trajectory. But one key driver is how the years of peak childbearing and peak human capital formation (education and job training) now directly conflict. Two factors typify why the post-industrial economy has curbed family formation: more people are going to school for longer, and many have higher standards for themselves as parents. Better approaches to public policy can help people build wealth over the long term, which can smooth out some of the inherent tradeoffs. But perhaps the biggest way we could reset the conversation around wealth, independence, and family formation is by revisiting some of our cultural expectations.

Family as Consumption

Through most of history, children were both an investment and an insurance policy. They were expected to help contribute to the family—first in the fields, then in factories. And as one reached the end of economic self-sufficiency, children were a backstop against penury in old age.

As our society has grown richer, we have cordoned off childhood from economic production. We became more able to guarantee seniors respect and freedom from indigence in the form of welfare state programs like Social Security. The economic rationale for having children as a hedge against poverty, therefore, is no longer as salient as it once was.

Similarly, cohabitation has made forming a permanent household less economically necessary. Marriage, formerly the only socially sanctioned way of enjoying the economic and personal benefits of sharing a roof and a bed together, has become more of a social statement or lifestyle choice than a partnership undertaken for its economic rewards (though there is still a “marriage premium” in wealth and earnings.)

And so marriage and childbearing have become closer to an act of consumption than one of production. When people marry or have children, they are just as often reflecting their personal values and self-conception, rather than aiming for the economic benefits. This realization doesn’t need to fill social conservatives with dread. But it should make them interrogate what cultural factors, often operating through the channel of economics and economic expectations, might influence those aspirations and desires.

Income, Wealth, and Housing

One major implication is that the relationship between fertility and income has moderated; in the 1980, poorer households were much more likely to have a child than their higher-income counterparts. But as having children has become more costly, and contraceptive technology has become more effective, low-income women now defer fertility just like their college-educated peers.

Wealth is closely linked to income, but it’s a broader, shaggier concept. Measuring wealth involves some amount of subjectivity in assessing someone’s assets, from artwork to investments to boats. But for most people, the biggest component of wealth is their house. Owning a home means having not just a place to lay one’s head, but an extremely large, undiversified investment, making up a large part of net worth and retirement planning. And housing can have a surprisingly direct effect on family formation.

As Jonathan Coppage and I once recapped for the late Weekly Standard, there is strong empirical evidence that local housing markets can have a direct impact on fertility. When house prices go up, homeowners feel richer, and their fertility rates go up. But those who are renting see more and more of their paycheck going to their landlord, and have fewer kids. In high-cost states like California, where a large share of young adults are renting, that can push already low fertility rates even lower.

This finding should inform our thinking about the relationship between intergenerational wealth and family formation. Most people see their income, and wealth, increase over their lifetime until retirement. Homeowners who turn 30 years of mortgage payments into significant equity stand to reap a windfall if they downsize to a smaller place upon becoming empty-nesters. On the flip side, the years when people have the lowest net worth tend to be their prime childbearing years.

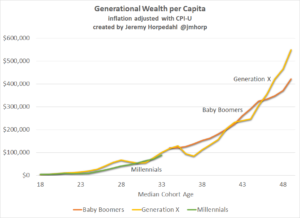

This dynamic over the lifetime can lead to some gruesome-sounding statistics. The Washington Post, for example, purported to show the “staggering millennial wealth deficit, in one chart,” indicating millennials owned a smaller share of the nation’s wealth than previous generations. But a group’s share of a total is largely a function of how many people are in that group and how old they are. The Baby Boom generation owns a large share of the nation’s wealth because there are, simply, a lot of them, and they’ve had a lot of time to save up.

Jeremy Horpedahl, an associate professor of economics at the University of Central Arkansas, retold the story of generational wealth looking at wealth per capita, rather than the share held, finding a more hopeful story: millennials’ wealth per capita appears on track to follow that of Gen X and the Baby Boomers before them, and perhaps even surpass them as student loan debt (which counts as a negative in their overall net worth) gets paid off.

Of course, this does not get us around the fact that the years of intensive human capital formation coincide with the years of prime reproductive capacity, driving increasingly delayed family formation. And even if the intergenerational wealth picture isn’t getting worse for young adults on average, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive to make it easier, particularly for those making below the median income, to earn a secure place in the middle class.

Because housing plays such a large role in household expenditures and retirement planning, any agenda that seeks to make it easier to form a family must include increasing the availability and affordability of owning a house. Some households will be better off renting, particularly those just starting out and yet to settle down, or empty-nesters looking to downsize. But home ownership, with its direct link to fertility and its heavy influence on long-term finances, is an important vehicle for creating equity and stability for many families. Unfortunately, our policy choices constrain that ability for too many.

Regulatory barriers, such as restrictive zoning overlays and environmental protections, push up the cost of housing, not just in high-cost urban areas, but even in Sun Belt cities that have seen rapid growth. (One could make a modestly tongue-in-cheek, though not entirely unreasonable, case that embracing restrictions on new housing is antithetical to conservative values; high rents, fueled by constrained housing supply, actively incentivize two single adults to cohabit rather than living separately before marriage.) In the abstract, conservatives should love the idea of getting rid of government regulation and allowing the market for housing to function more freely. But two culprits often stand in the way: the culture wars and economic self-interest.

In 2020, a nascent pro-housing agenda from Sec. Ben Carson’s Department of Housing and Urban Development was squelched by the Trump administration, influenced by populist commentators like Tucker Carlson who accused the plan of seeking to “abolish the suburbs.” And making housing more affordable can be in tension with the view that housing should be an investment and key part of a family’s nest egg.

The “Yes In My Backyard,” or YIMBY, coalition can sometimes do itself no favors, combining the insufferability of a self-righteous Twitter mob with disdain for real tradeoffs around neighborhoods and aesthetics. YIMBYs should seek to persuade, not browbeat, stakeholders into realizing that duplexes, accessory dwelling units, and more houses being built on more land is essential in helping young families afford the cost of living.

Debt and Fertility

A wealth-focused angle also informs how we should think about debt and family formation. Only looking at one side of the debt–asset equation obscures the value of being able to borrow. For example, many who take out student debt do so in the expectation of increasing their lifetime earnings potential, which can be obscured by focusing on point-in-time estimates of debt held. In fact, men with student loan debt have historically been more likely to get married, because their advanced education signaled seriousness and higher earnings potential.

Today, the supposed albatross of student loan debt is cited to justify President Biden’s unconstitutional $10,000-per-student loan forgiveness program, and some boosters have pointed to anecdotal evidence that beneficiaries will now have the financial freedom to get married. But most of the available research suggests that large balances of student loan debt only mildly, and indirectly, reduce the likelihood to marry; thus President Biden’s loan forgiveness likely won’t lead to an upsurge in wedding bells.

There is a better argument for addressing the costs of having a child: parents shouldn’t have to go into debt to provide for their child. Parents bear the cost of childbearing individually, in the form of diapers, formula, and more living space, as well as potentially forgoing raises and promotions—the unseen, but real, opportunity cost of parenthood. Meanwhile, society benefits in the form of future workers, soldiers, and entrepreneurs—the classic case of what economists would call a positive social externality.

De-escalating Luxury Parenthood

The most straightforward way to ensure parents don’t bear an excessive financial penalty for raising a child is to provide them with some financial assistance in the form of a child benefit or tax credit. But these programs work best as a form of income-smoothing; a more generous child tax credit should not, in itself, be a pathway to greater wealth.

And the perceived cost of raising a child is driven just as much by what people think they should have as by what they need. Sociologist Andrew Cherlin’s famous insight about marriage may be increasingly applicable to parenthood as well. Whereas prior generations saw the institution of marriage as a “cornerstone” upon which to build a life together, Cherlin wrote, many couples, particularly college-educated ones, now see it as a “capstone,” marking the end of a successfully navigated early adulthood.

Similarly, mothers in prior generations may have chosen, or had thrust upon them, parenthood in lieu of a career. But we now have higher opportunity costs of parenthood, technological advances that enable greater choice in when and how to have a child, and a cultural shift that increasingly finds meaning in work, identity, or causes, rather than family, faith, or community. Some of this stems from a laudable desire to provide for a potential future child. But the idea that having a child is now also a “capstone,” to be fulfilled only when everything else is in order, is seen in both college-educated and working-class women alike.

So in some respects, the most important step to address the perceived desire to delay childbearing until one is financially “ready” would be to lower the arms race around parenting. Many parents, particularly college-educated ones, feel that the burden of the role has grown heavier. No longer is it enough to send kids out into the woods and hope they’re home by supper: “parenting,” as a verb, now means curating an intensive experience of human capital formation. Garey and Valerie Ramey’s 2010 paper traced some of the economic mechanisms at play in creating this new “rug rat race”: intensive college admissions drive high-cost enrichment activities in high school, and on down to early childhood.

The cultural ratchet only works one way. Trying to raise a child on a 1960s diet, in 1960s clothes and with 1960s car safety, would result in getting Child Protection Services called on you. It’s a good thing to have healthier, safer kids. But a wealthy society that can afford a lot of expensive services and gadgets for parents resets the expectation for what is “normal,” even if it’s not necessary, and raises the implicit bar for what a couple needs to be “ready” to have a child. A parental compact to say no to $2,000 strollers wouldn’t just benefit their pocketbook, it would strike a blow against “keeping up with the Joneses” and in favor of sanity.

In a post-industrial society where marriage and fertility are expressions of values, rather than buttresses for economic security, policies that strive to make it as easy as possible for people to get married and have children should be at the forefront of the agenda. Ensuring an ample supply of housing would be an important piece of the puzzle in reducing the financial barriers, as would a stable child benefit for all households with a worker. But just as the shift from a “cornerstone” to “capstone” model of thinking about marriage and parenthood wasn’t primarily driven by policy, no amount of state exhortation or investment can take the place of a pro-family culture, from media outlets to religious institutions to schools.

An all-of-the-above approach to making family life more achievable will make it possible for more individuals to generate wealth—both the kind that’s measured in dollars and the more important kind measured in the warmth of extended family and strong communities.

Patrick T. Brown is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where his work with the Life and Family Initiative focuses on developing a robust pro-family economic agenda and supporting families as the cornerstone of a healthy and flourishing society.

Patrick T. Brown is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where his work with the Life and Family Initiative focuses on developing a robust pro-family economic agenda and supporting families as the cornerstone of a healthy and flourishing society.