Published August 1, 2019

Somewhere in Putnam County, N.Y., southbound to New York City on the Taconic Parkway, the odometer on my 2004 Volkswagen Golf hit 250,000 miles. I felt like Chuck Yeager breaking the sound barrier.

The car, silver in color, with a raffish crease in the right front fender (a sort of dueling scar) and a cigarette burn in the driver’s seat, has my affection and respect. Over time, it has become my power animal—my objective correlative, almost. Like me, it has had several of its engine parts replaced. My heart’s got six bypasses stitched into it, so that I and the VW (with its new fuel pump, timing belt, alternator and exhaust system) are inspirations to each other—heroes of patched-up longevity.

Despite its age and miles, I’d rather drive it than anything newer or fancier. If I were offered a new Mercedes in trade, I guess I’d take it, because I’m not a fool. But I’d regret it, too, and would tell myself that I had sold out.

The engineers who put together the machine achieved an unexpected perfection of relationships so that, for example, its weight and power are harmonized (each, so to speak, understanding the other), and the thing jumps from the starting gate like a thoroughbred—like Seabiscuit. Its primitive excellence is a remnant of an earlier world.

The car’s manual transmission connects me to its energies and motions. Among other things, it returns me (in the dreamy subliminal dynamics of gears and speed and memory) to the time when I was 19 and drove west across Kansas in the middle of the night, the Volvo 544 coupe plunging through violent prairie line storms—wild, soundless lightning, lashing rain. The Volvo’s manual transmission was like my Volkswagen’s—fluent and, as it were, comprehending—as I ran up and down the gears, my brain integrated with the living engine, left foot working the clutch, right foot the accelerator, left hand the steering wheel and right hand on the knob of the gearshift: man and beast colluding sweetly and roaring along through the tremendous electricity of the Kansas night and the bright meteor showers of rain. I felt happy and free.

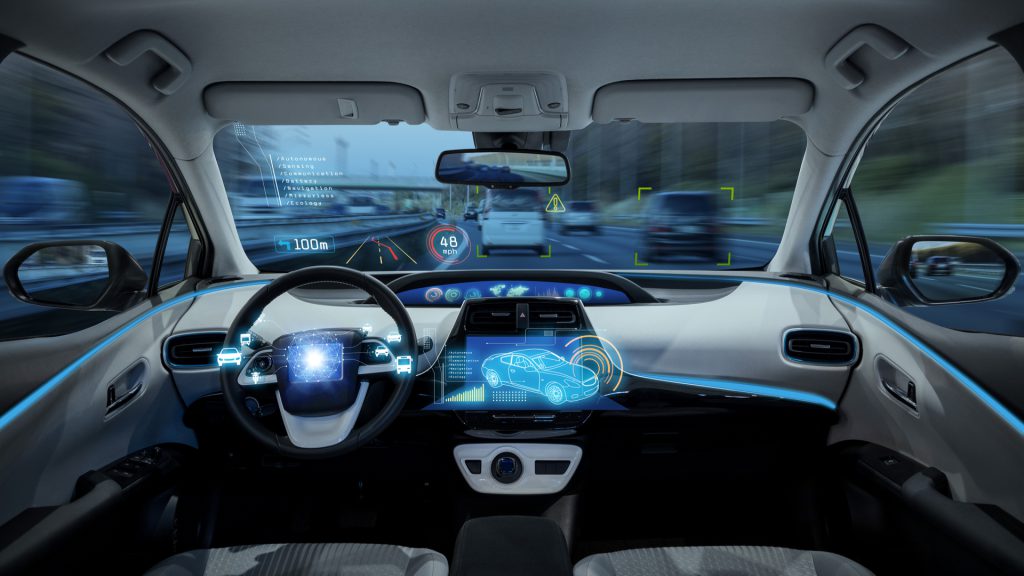

The Volvo yesterday, like the VW today, was modest. Luxury was not the point. Luxury is a mug’s game—a moral disability. The point was something we did not sufficiently love—the purity in the execution, in the skills, the simplicity of the gears. Now luxury offers us cars that drive themselves while we doze off. I wonder if that’s a good idea. Someday we may need the earlier skill.

Mr. Morrow is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.