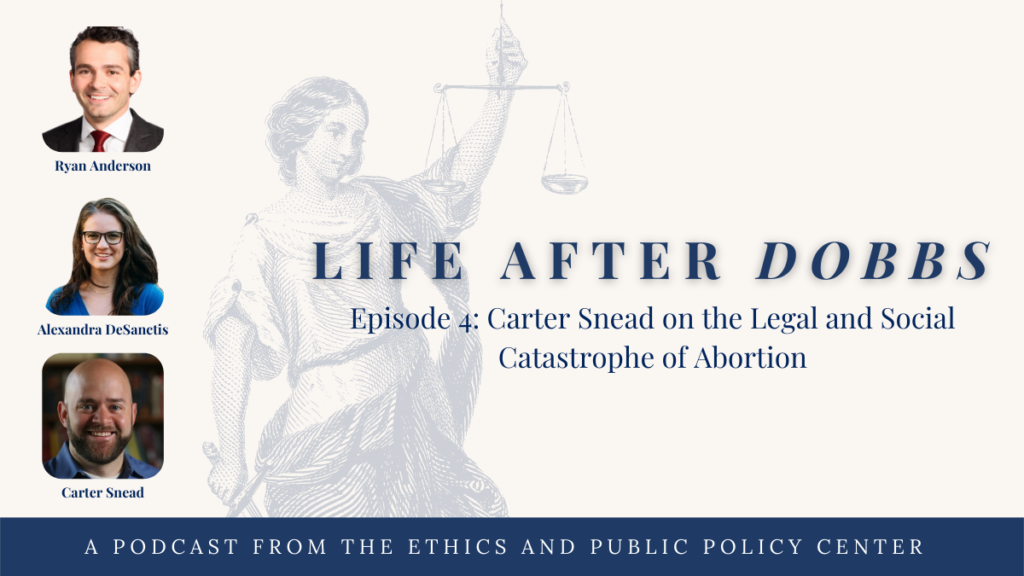

In the fourth episode of EPPC’s Life After Dobbs podcast, hosts Ryan T. Anderson and Alexandra DeSanctis talk with O. Carter Snead about the meaning of embodiment and vulnerability, why pro-abortion arguments that pit mothers against their children are fundamentally misguided, how abortion corrupts the practice of medicine, and more.

Listen on:

Show Notes

Guest

Follow Carter on Twitter: @cartersnead

Click here to learn more about Carter’s book What It Means to Be Human: The Case for the Body in Public Bioethics.

—

Hosts

Ryan T. Anderson (@RyanTAnd)

Alexandra DeSanctis (@xan_desanctis)

Order Ryan and Xan’s new book Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing today!

Click here to learn more about EPPC’s Life and Family Initiative.

—

Life After Dobbs is a production of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. For more information, follow us on Twitter (@EPPCdc) or visit our website at eppc.org.

Produced by Josh Britton and Mark Shanoudy

Edited by Sarah Schutte

Art by Ella Sullivan Ramsay

with additional support by Christopher McCaffery and Alex Gorman

Episode Transcript

This transcript was automatically generated and has been lightly edited for clarity.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Thank you so much for joining us today, Carter, for this conversation.

Carter Snead:

Oh, it’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me on.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

So we want to start with kind of getting to the root of the problem here. We all know–or pro-lifers, I suppose–are willing to acknowledge that abortion kills an innocent human being. We know that’s always morally wrong. That’s the basic kind of the heart of the pro-life case, but can you go a little bit deeper for us and talk about kind of the fundamental problem with abortion, by which I mean how it contradicts a rightly ordered understanding of what it means to be human.

Carter Snead:

Yeah. If you look at Justice Blackman’s opinion, and if you look in Roe v. Wade, and also certainly the opinion of the plurality in Casey, they echo very much implicitly–they don’t cite it directly–but they very much echo implicitly the philosophical literature on abortion which basically tries to justify abortion according to two different arguments. One of which is the bodily dependence argument. The argument is that the mother has the right to eject the intruding stranger from her body and, and to not extend the support of her body, if she wishes. The Judith Jarvis Thompson violinist argument, which your listeners are probably familiar with, is the kind of canonical example of that. But then you also have a kind of personhood argument making the claim that the unborn child is not a member of the moral and legal community, even though, as we all know, of course some abortion rights activists deny this, but the science is not on their side, that we all know that the child in the womb is a living human organism. It’s a living member of the human species. But the personhood argument seeks to constrict the circle of the moral and legal community and, and rule out certain living members of the species from that circle, and therefore exposing them to a world in which they lack the protection of the law, including the laws against private violence. And they try to make the argument–they try to divide the world up into persons and nonpersons based on different criteria that of course are set by the strong and the privileged, according to their own interests. They frequently relate to cognitive capacities. You have Michael Tooley, you have Maryanne Warren who try to associate the essential characteristics of what it means to be a person with the capacity to formulate and pursue future-directed plans, to have desires that you can express and pursue. And to your question, both of these arguments, both the, the bodily dependence argument and the personhood argument trade in assumptions about what it means to be human that are, I think, false and impoverished. In the book, I name the kind of false anthropology as expressive individualism, namely the idea that the basic unit of human reality is the individual person shorn of all connections, abstracted from all relationships and connections, and whose highest flourishing is to discover inside, you know, by thinking and introspection and searching the depths of one’s own sentiment, discovering our own authentic, original truth, expressing it, then configuring our life plan accordingly. And in this framework, all relationships are transactional. There are no unchosen obligations. And the world basically is a world of atomized individual wills that are seeking their own goals that they invent themselves, and they encounter other wills sometimes in a collaborative way, other times in relationships of strife, where they have to overbear the other to realize their own objectives. And that’s really the vision that underlies the theories of personhood, bodily dependence, and frankly, the arguments in Roe and Casey. They describe the human context in which the issue of abortion arises as a conflict of vital zero-sum conflict among strangers. The mother is not a mother. The mother is simply a woman who has a womb that belongs to her that’s her property. There’s an intruding stranger that she did not invite in. And so the question is, what do you do? And it’s not surprising when you frame the issue as a conflict among strangers fighting over scarce resources that properly belong to one of the two strangers. And when one of the strangers is deemed to be a person and the other one is somehow sub-personal, which is implicit in the Roe and Casey decisions and the philosophical literature that undergirds them, it’s not surprising that what the Court did was say, and what abortion advocates argue for is a right to private violence, to use private violence for the one party to fend off the other one. I mean, in Thompson, she makes analogies to people fighting over a coat that’s necessary to survive the winter that belongs to one of the two parties. Well, that’s, that’s how abortion, the human context of abortion is conceived and framed by the abortion-rights movement and by the jurisprudence that hopefully will be overturned very shortly. And what I suggest is that in fact, that completely misunderstands the human reality and the human context of this sometimes tragic circumstance. It’s not a conflict among strangers fighting over scarce resources. It is in fact a mother and her child who already exist in a relationship, an embodied relationship with one another, which brings with it certain kinds of obligations, unchosen obligations and unearned privileges. Children don’t have to earn the right to be cared for by their parents, parents don’t transact and contract for the obligation to care for their children. It’s intrinsic to the relationship itself. And our reaction to the sometimes tragic circumstance of these pregnancies is different if we think about it through that lens. If we think about it as a conflict involving a mother and her child, any decent person would rush to the aid of the mother and child and provide them both with support and care and love as the pro-life movement seeks to do, as opposed to saying, okay, one of you has the right to kill the other one to fight to possess the thing that you properly own.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Carter, that’s great. And can I get you to draw out the last 30 seconds of what you just said a little bit further? Because in the book and, you know, Xan and I love your book, we cite it all throughout our own book. When you know, any reader of both books, we’ll see, it’s heavily influenced our own thinking and our own writing. And you helpfully describe two competing anthropologies and I’ve heard you give public lectures where you lay out the two competing anthropologies and Xan’s opening question really got you to elucidate what the bad anthropology is–the expressive individualism, the dualism, and those last 30 seconds there, you kind of started articulating what the alternative anthropology is. Could you say more about that? Do we have a name for the alternative anthropology?

Carter Snead:

In the book I call it an anthropology of embodiment. Because the problem with expressive individualism, I mean, it does capture something true about our lives. We are free, we are particular, but that’s not the full truth of who we are. And what expressive individualism ignores is the fact that we live our lives as embodied beings. We’re adynamic union of mind and body, not merely disembodied wills. Our body is not purely instrumental in service of our will. In fact, our body is an essential part of our identity, which also of course includes our will and our mind integrated in a kind of seamless way. But as Gil Meilaender says, the body, at least in this life, is the locus of personal presence. And if you ignore the body, and if you ignore the fact that being embodied beings has certain kinds of entailments, it makes us vulnerable because we’re fragile beings in time with corruptible bodies. And that stands us into a certain kind of relationship vis a vis one another, I argue, because we’re vulnerable, we’re dependent upon one another. We’re reciprocally indebted to one another, and we’re subject to natural limits. And by reflecting on those entailments of embodiment, in the book I argue that what an embodied being needs is not the freedom of the unencumbered will and access to violence to fend off intruders, but rather what we need to survive and flourish as embodied beings are what Alasdair MacIntyre calls networks of uncalculated giving and graceful receiving, which are composed of people who are willing to make the good of others their own good for the sake of the other, not seeking anything in return, not in a transactional way. And the most pristine example of this is the family, right? Like, as I said a moment ago, parents don’t take care of children because they are obliged by contract to take care of the children because of some–it’s not a creature of consent. It’s implicit in the relationship itself. A parent’s job is to make the good of their child their own good, and the child doesn’t have to earn the right to be cared for in that relationship. But it’s not simply the family. It extends outward to communities. And even more broadly than that. And it seems to me that in order to survive, basic survival depends on someone making our good their good, none of us would be on this podcast right now, if someone, probably our parents, decided to care for us without seeking anything in return. But more than just for basic survival, I argue it teaches us the thing that we’re supposed to be. That is the kind of person who can make the good of another our own good. And to put it sort of more succinctly, in the book I argue by virtue of our embodiment we’re made for love and friendship. And there are certain kinds of virtues and practices that are essential to strengthening, creating and shoring up these networks, namely the virtues of graceful receiving and unconditional giving. And unconditional giving includes the virtues of just generosity, hospitality, misericordia– that is making the suffering of another your own suffering, to seek to heal and comfort them. But if that’s not possible, merely to accompany them. And of course, the virtues of graceful receiving which include, chief among them, gratitude from which follows humility, solidarity, respect for human dignity, openness to the unbidden and other goods as well.

Ryan T. Anderson:

I love that. And you say it so beautifully, really, you know, inspiring. And I want to just ask a quick follow-up, and maybe it’s not so quick. It’ll be quick for me to ask it. It might be longer for you to answer it. You haven’t mentioned God or religion in either of these anthropologies. And so I just wonder at the anthropological level, the philosophical level, what role does God and religion play in the competing anthropologies and then in the applied level of, you know, as applied to abortion, what role do you see God and religion playing?

Carter Snead:

Yeah, no, it’s a really great question. You’re right–in the book, I don’t appeal to God or religion. However, everything I say in the book is coherent with, and of a piece with, the teachings of, certainly of the Catholic faith, which is the one that I’m most familiar with, the one that I profess and is the most important thing to me. But I wanted to write the book in a way that made it accessible and intelligible to a secular audience. And I think there’s a way to kind of describe, and again, the sort of, the philosophical level, the book is not a comprehensive work of philosophy or theology. It’s basically, it appeals to people’s experience and their practical wisdom to confirm the arguments that I’m making. I want people to understand, if you think about your life, if you think about it in a non-idealized, in a realistic way, and you think about the arc of your life, both in the past and the future, you realize that your embodiment matters and it matters in these ways that–and the brute reality is for us to survive and flourish, we need these networks we need–but basically,, a more succinct version of what I’m talking about is the parable of the good Samaritan, right? When I was talking to Harvard University Press about the cover art they were very generous to listen to me, but at the end of the day, it was their call as to what the cover art was. I said, let’s get a beautiful, you know, rendering of the good Samaritan, because that kind of captures the anthropology of embodiment. The idea of who is, you know, you were called to care for your neighbor. We’re most human when we’re taking care of each other and taking care of each other. Not because we’re trying to get anything for ourselves, but because that’s, that’s what it means to be and flourish as a human being, to care for one another. And they said, well, we appreciate that. And then they went with a picture of two, like weird nude people on the front, not literally, but like, I mean, it’s a good cover. I’m not criticizing the cover, but it’s a science fiction looking…I would never dream to consider, to criticize the amazing people at Harvard University Press. They’re fantastic. But in any event, they really are fantastic by the way, the people that I worked with are amazing. But I should say though, that a Catholic person, or a Christian person, or a person who you know, is adherent to any of the faiths that profess similar truths I think could feel very comfortable reading the book, thinking about the arguments and contextualizing within their own faith. Now, as I said earlier, a moment ago, it’s not, again, the book doesn’t argue, doesn’t derive first principles. It doesn’t go that deep on purpose. It’s a book about, it’s a kind of proposal to, for fellow citizens to think about in a kind of pluralistic society, but if you were to press, the deeper question is why do we take care of each other? I think that’s what it means to be a human being, and love and friendship are at the core of what and who we are. You know, is it possible to maintain that kind of a normative posture without ultimately appealing to God? And maybe not just any God, but the God of the Bible? You know, that’s a very hard question and some very smart people have suggested that it’s not possible. Gil Meilaender I think is the most interesting person to read on that front.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

I want to thank you for those really helpful thoughts. And I, I really want to add to what Ryan said about how helpful your book was in writing ours. And not only that, I would really encourage readers, or listeners I suppose, to read it, because it was formative for my thought about abortion and about just human life in general, what it means to be human. So formative that the seeds of what ended up being the thesis of our book really came to me while I was reading yours, so I’m really grateful for your work. We are here today in a sense because of it. But switching gears a little bit, we want to talk about kind of our laws, and you’re an expert on this–Roe and Casey, what they said. But more than that, kind of how the flaws of Roe and Casey have negatively affected our legal system and how undoing them is necessary really to rectify those harms.

Carter Snead:

Yeah, I would say, in addition to the horrible body count–let’s just be clear with your listeners. I’m sure they already know this, but Roe v. Wade for the first time by the Supreme Court in American history, declared that our Constitution itself, the very document that creates our republic and the very document that defines our government and defines the relationship between the government and citizens to a large extent, that document itself declares the unborn child to be a non-person. Despite what Roe v. Wade says–a legal non-person–Roe v. Wade says, oh, we’re not gonna take a position on whether or not the unborn child is a person. We don’t think it’s a person within the meaning of the 14th Amendment, the equal protection clause or the due process clause, which was not a very compelling interpretive exercise in Roe v. Wade. It’s like, he looks at the five or six other uses of the word “person” and concludes that since they don’t refer to prenatal human beings, this must not either. Put that to the side, you don’t have to declare the unborn child to be a person within the meaning of the 14th Amendment to treat the child as a person in the laws of the separate states, or even by the federal government. You could treat the child as a person, provide the same protections that persons have. We protect other entities, non-human entities all the time with the full force of the law. I mean, you can imagine the Endangered Species Act, you could imagine all kinds. There are ways in which we protect certain class pf living beings. And up until that point from before the nation’s founding, the common law of England, and then it was especially clear in the middle of the 19th century when more was understood about human embryology and states started to codify bans on abortion from the moment of conception, which by the way was contemporaneous with the ratification of the 14th Amendment, which is the source of authority the Court falsely claims gives a right to abortion. So just on its face, it’s absurd. If you have any limited, if your interpretive method of reading the Constitution is restricted in any way, you can’t possibly argue that an amendment that was adopted in 1868, ratified in 1868, at a time, an abortion was basically illegal everywhere and became even more restrictive in the year after the ratification by the various states, that somehow that language precludes states from protecting unborn children, nobody on the Supreme Court seriously thought that until the latter part of the 20th Century. And what Roe v. Wade says is: states, you may not adopt one theory of life and protect the unborn child as a person because of the burdens on women of unplanned pregnancy, but also, as the court makes clear, unplanned parenthood. The burdens on women that are imposed by unplanned pregnancy includes, according to Justice Blackmun, not just the physical and psychic burdens of pregnancy itself, but the burdens of raising a child that is unwanted, and not just on the mother, but on the whole family and community of the unwanted child. And then Doe v. Bolton, decided the same day as Roe v. Wade, in sketching out what constitutes medical judgment in this space for whether abortion is needed or not, it includes not just physical or emotional health, but familial health. So on the one side, and again, just to be clear, the right to abortion emerges in Roe v. Wade from a balancing of the Court’s understanding of the burdens on women on the one hand and the state’s interest in maternal health and the life of the unborn child on the other, which they describe as potential life, which is biologically incoherent, because it’s actually a life present in process. It’s not potential life. But nevertheless, they say by weighing these two competing interests, we conclude that the mother’s interests are so significant and the state’s interests are so diminished that the state’s forbidden from treating the unborn child as if he or she were a person. And the violence that that does–putting aside the 60-plus million abortions that have happened since 1973–by forbidding the states from protecting unborn children. If we think about it for a moment, what it means for the Supreme Court of the United States to say that our Constitution is the thing that forbids us from protecting the weakest and most vulnerable, that that is a stain and a corruption that that has to be removed. It’s not enough that–that has to be declared null and void, which I hope and pray will be the case, especially if the draft opinion of Justice Alito becomes the opinion of the Court. So Roe v. Wade obviously led to 60-plus million abortions in America. It corrupted and destroyed our Constitution. I mean, your entire book is about how abortion destroys everything it touches. It destroys the parental relationship. It destroys the practice of medicine. It destroys the law. I mean, Roe and Casey and abortion jurisprudence generally was described as a post hoc nullification machine by some justices, saying no matter what, the settled laws in a particular area, if the topic is abortion, the outcome of the case is going to bend in the direction of promoting abortion. Even if that means departing from well-settled legal principles, and Justice Alito goes through that in his draft opinion, he talks about the law of standing. He talks about First Amendment law. He talks about res judicata, which is a civil procedure principle. Even the context of stare decisis has changed and bent if the topic is abortion, as we saw in Planned Parenthood versus Casey.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Carter, you just gave the perfect segue to the next question, because you know, you mentioned that our book touches on everything that abortion has harmed, and it harms everything it touches. Our fifth chapter goes through how it’s harmed constitutional self-government but then the prior chapter, chapter four, is how it harms medicine. And you had just mentioned that and we want to get you to say a little bit more about that because it seems like the logic of abortion on demand has not been contained to abortion, that that logic has corrupted the medical profession. And you can see this in how it’s extended to recent pushes for the legalization of physician-assisted suicide, euthanasia, embryo destructive research. I know you kind of really got your professional start working on the President’s Council for Bioethics during many of the debates surrounding cloning and embryo destructive research. And your book covers many of these questions. So could you help our listeners understand how that logic has played out to these other areas?

Carter Snead:

So to understand the corruption of the practice of medicine by abortion itself, we have to start with what medicine is. And it’s, I mean, so medicine is a profession, right? That’s the kind of most important insight. Medicine is a profession, it’s not simply a set of skills or techniques that are brought to bear in service of the desires of the customer sometimes called, that we normally call patient, right? Ed Pellegrino, who was the chair of the President’s Council on Bioethics after Leon Kass, Leon Kass himself, Gil Meilaender, but Ed and Leon, especially, because they are trained as physicians, write very beautifully, especially Leon about–I mean, Ed’s great too, they’re both great–about about what medicine is and where the norms and the ethical principles come from. And it’s not necessary to get into the weeds on their kind of internalist perspective on how the norms and ethical principles emerge from the practice itself. What’s more important to focus on is the basic point that Gil Meilaender also talks about that a profession is different from a mere set of skills that you apply in service of whoever pays you. A profession is organized around a good to be advanced, a good to be professed. Everything you do is accountable to that good. Everything you do is understood through the lens of pursuing that animating good. And the good of medicine, the practice of medicine, is the good of health is the ministry to health. It is to serve the health of the patient by the lights of the physician, according to his or her training and expertise, but also according to their fidelity to the ultimate good of their profession, which is, which is the definition of health, which I think most people take to be the well- functioning of the organism in its species-specific context. It is: what does a healthy organism look like? It’s a kind of objective reality. It’s not merely subjective. It’s not merely defined by the desires and the wishes of the patient, but we’ve seen a transformation in the practice of medicine with, and again, the story of the practice of medicine and medical ethics in the United States is an interesting story. It sort of begins with total confidence and trust in physicians. Physicians adopted a kind of paternalistic posture towards their patients and that was fine with the patients because they trusted the physician and they understood the physician was almost sort of part of their family and in a kind of priestly role ministering, not just to the health of the the individual, but to the whole family itself and to the person’s well functioning in a broad and holistic sense. But then gradually over time and kind of ironically, as physicians became more technically adept at mastering the tools of their profession, especially different pharmacological interventions, different genetic advances, it was perceived rightly or wrongly that physicians were becoming more humanly distant from their patients as they were becoming more technically skilled. And so the outcomes were in large part better for patients, but patients felt left out of the decisionmaking, felt like the doctors were thinking of them and treating them as objects to be worked on and puzzles to be solved through mechanistic techniques in a kind of a reductive way rather than as people to be cared for. And so there was a backlash and the normative embodiment of that backlash was the kind of emphasis and the rise of informed consent and patient autonomy, which was meant to push back against what was perceived as an overbearing paternalism and a kind of loss of the human connection between doctors and patients. But what it seems to be the case, and one could probably make the argument that this appropriate concern for autonomy of the patient and being involved in their medical decisionmaking was can be, can be taken too far. And the good of autonomy can grow so large that it can overwhelm even the central animating norms of medicine itself. And the idea could become that really doctors are just service providers for whatever the patient happens to want and the desires of the patient are what define what the doctor does and doesn’t do. And we see this in the abortion context, we see this with the sort of the highly politicized leadership of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists who are pushing back against conscience protections for doctors. And I think that the freedom of the physician to practice medicine in accordance with the good of medicine, namely the good of health, according to his or her professional judgment is actually not even best framed as a matter of conscience. I mean, of course it involves conscience, but it actually just is a matter of what it means to be a doctor, to practice medicine, to serve the good of the patient as you see, in light of your training and the good of health. And an abortion, in many, many doctors’ opinions–and if you look at the surveys, not many doctors, not many OB-GYNs will actually perform abortions. It’s despite the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists prioritizing abortion, really, I should say the leadership because the membership, I think, has a different view than the leadership, but the leadership kind of takes the official positions. And it’s radical. They say that, you know, you should be made to perform an abortion if you’re not if there’s nobody else to do it, or you should be made to refer someone for an abortion, even if you believe correctly, that that’s the intentional killing of an innocent human being and a doctor could say, and it’s not a matter of conscience, but a matter of professionalism. Look, I don’t think that abortion in almost any situation actually serves the health of the patient. It’s an elective procedure to take care of a kind of social problem. And again, it’s blessedly rare that abortions are needed to preserve the physical health and for sure, the life of the mother. Studies, including from the Guttmacher Institute show that most abortion decisions are made in light of other concerns, concerns about not wanting to, or being able to care for the child and not being concerned about financial issues or being concerned about the interference that a child would present to one’s future plans. And that, by the way, points us as pro-lifers in the direction of things that we need to do and how we can reach out and care for those women in crisis and those families in crisis and things that we need to do to try to help them choose life and to care for their babies or to make an adoption plan if that’s what they decide to do. And so the bottom line, though, is that I think that this kind of emphasis on autonomy overall has led to diminishment of the notion of medicine as a profession. And as you say, it’s not limited to abortion. I mean, you have–someone shows up, they say, doctor, I want you to prescribe me with barbiturates so I can kill myself. You know, thank goodness the AMA still takes the view that that is a corruption of what the good of medicine is itself and the end of medicine is healing and comforting, and to facilitate and be handmaiden of death, whether it be an abortion or assisted suicide, is very antithesis of that.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Yeah. It’s very interesting that you raise ACOG and kind of the pro-abortion turn of a lot of these major medical organizations. You’re definitely right that most doctors, most OB-GYNs do not agree with these groups. But we talk a bit in the book, we have a whole chapter on medicine, and we talk about the history of how ACOG and pro-abortion kind of elite doctors were the chief drivers actually of the pro-abortion movement around the time of Roe. They lobbied the Supreme Court very heavily and I think were decisive in this argument that, you know, if a doctor thinks that a woman needs an abortion his judgment or I suppose her judgment should trump, right, the doctor should get to decide not the government. That was the line. It was very doctor-centric, very much about the autonomy, the rights of the doctor to exercise his or her medical judgment. And now if a doctor has a medical judgment [that] actually abortion isn’t necessary, ACOG says, oh, too bad, do the abortion anyway, right? So it’s really all about just promoting abortion, it’s not actually about doctors’ consciences or what they think is medically best. So switching–I guess we’ll go back to the law for a moment. Last December, I think there were some reports that the attorney general of Wisconsin had said he would not enforce the state’s existing prohibition on abortion if Roe v. Wade were overturned and that law was able to take effect, I’ve seen similar things cropping up here and there. Essentially progressive people in charge will not enforce pro-life laws, even if they’re on the books, what are we to do about that? What can we do?

Carter Snead:

So this is, this is the great unmentioned premise of the Texas law that was so widely condemned in the popular press. The heartbeat law that had a very unusual mechanism of forbidding the state from enforcing it, instead transferring that authority to private citizens who would bring civil suits against everybody who’s involved in the provision of an abortion after a heartbeat’s detectable, except for the mother herself, right? She was immunized from civil suit in that case, as mothers are immunized from criminal liability in every modern abortion law that I’m familiar with. So there was a whole group of district attorneys and prosecutors in Texas who signed a letter saying they would never enforce pro-life laws in Texas. And so this Texas legislature decided they had to figure out a way to get the law enforced, and they came up with that idea, the civil lawsuit idea. There are other approaches that are more conventional. One could simply pass a statute that says that if you have a faithless district attorney or a faithless attorney general that the governor or somebody else designating some other person, or maybe even a hierarchy of people, a list of people who have the authority to enforce the law. But yeah, this is a real problem. And you see this, as you say, there’s all kinds of–I mean, imagine, you know, honestly, it’s what it’s reminiscent of is the civil rights movement of the sixties. It’s Bull Connor, it’s George Wallace standing in the courthouse door, preventing little black kids from going to school with white kids. It is a last gasp of refusing to participate in, to abide by the law, because you’re so committed to, in this case, abortion, which is by the way, also a form of radical discrimination, ruling out, singling out one segment of the human family for radical discrimination to remove from them the protection of the law. And you know, a lot of these, a lot of these commentators these days are trying to connect white supremacy and racism to the pro-life movement. When in fact, as we all know on this call, probably your listeners know too, the truth is almost exactly the opposite. I mean, Fannie Lou Hamer was a pro-life civil rights leader in Mississippi at the same time George Wallace was advocating for abortion because he didn’t want African Americans reproducing. Modern white supremacists like Richard Spencer love abortion because they understand that that black and brown and poor people are the primary targets for abortion. I mean, it’s literally true–Margaret Sanger’s a kind of complicated figure because I’m not exactly sure what she thought about abortion. She criticized it publicly. I don’t know exactly. She was not a proponent of abortion, let’s just put it that way, officially. But she, nevertheless, I mean, was the founder of Planned Parenthood. And a lot of people took her thinking and ran with it on the question of abortion. And she literally gave a speech to the Ku Klux Klan women’s auxiliary in Silver Lake, New Jersey in the late 1920s. Now people defending her say, well, she wasn’t a racist. I’m not gonna speak to what her views were, but for some reason she thought she would find a receptive audience in the Ku Klux Klan women’s auxiliary. And that’s, I think, indisputable. And so the effort to try to hang around the necks of the pro-life movement this notion of white supremacy is sort of diabolically false

Ryan T. Anderson:

In in the third chapter of the book we look through how, how abortion particularly harms, you know, segments of the population that are already marginalized: people of color little girls, elevated discriminatory rates of abortion, people with disabilities diagnosable in the womb. And we cite Richard Spencer. We cite Margaret Sanger. You know, in Sanger’s case, it was much more a push of contraception for eugenics purposes. Obviously Spencer has embraced abortion for similar purposes. But we’re running out of time, and so I want to kind of pivot towards a wrap up question. You mentioned earlier that the name you would give to the alternative anthropology is an anthropology of embodiment. You also write beautifully in the book [that] the truth of what it is to be a human is that we belong to each other. And that was the theme of your conference this past November at Notre Dame. Can you give some closing reflections on what do we, as a pro-life movement, as, you know, an American political community need to do post-Roe assuming that that’s what Dobbs gives us, a post-Dobbs, post-Roe world. What do we need to do? Give us some marching orders.

Carter Snead:

Yeah. So it’s funny, the person who said that, the person who said the core problem (this is a paraphrase) in the world is that we’ve forgotten that we belong to each other, was Mother Teresa. And she sort of is in my mind the most inspirational figure for what I think we have to do next in terms of not just what she did in terms of caring for the poorest of the poor and the people that no one would even look, look at much less help in the slums of Calcutta. But the way that she did it, the way that she did what she did was so transformative and so countercultural, and so kind of shocking. I mean, you and I and Xan are in the kind of argument business. We make arguments, we read things and we critique arguments, and that’s important. I’m not under valuing that, but there’s, I don’t like the chances of mere argumentation for changing hearts and minds of the most hardened committed people to the issue of abortion, especially, especially those people who have tragically, and there are many of them, have had abortions in their lives. They’re post-abortive, and it’s sort of unimaginable to even suggest that what they did was the reality of the matter, taking the life of their own child. So we have to really practice unconditional love, the likes of which Mother Teresa showed us–caring for others, including especially those that we disagree with as if they were Jesus himself. Okay. So now I’m gonna get religious on you. As if, I mean, the way the good Samaritan acted, right? So we need to, of course, take care of moms and babies. Of course we need to, and to their credit, the pro-life movement has been at the forefront of that forever. And we need to double down on that. We need to care for moms and babies and children, we need to do so in a way that is creative and thoughtful and is not, doesn’t bind ourselves to political orthodoxies or dogmas and [political] commitments, or procedural commitments, political ones. But I think even more so with people that we disagree with, people will know who we are by how we love them. And it seems to me that you can melt someone’s heart by actually loving them. And by saying to them, look, I understand that you argue for something that I consider to be unspeakably horrible, but it doesn’t change the fact that you’re a human being and the core of the pro-life movement is that everybody matters. Everybody counts. Everybody belongs no matter who you are, no matter what other people think of you, no matter how weak you are or vulnerable you are. And that sort of openness and hospitality and love, unconditional, is something that we have to translate in our interpersonal relationships with everybody. And so it’ll shock and it’ll be so countercultural, and it’s not to say it’s easy, and I fail at it all the time more than, I mean, almost always, right.? It’s rare to even be marginally successful in this. But the truth of the matter is we have to do it because that love, that self-emptying love, is what changes the world. Not arguments, although arguments are important to include.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Beautiful. Thank you, Carter.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Yeah. That’s a wonderful way to wrap up. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been a wonderful conversation, Carter.

Carter Snead:

My pleasure. Thank you guys.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Thanks for listening to life after Dobbs, Ryan and I are co-authors of the new book, Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing, which you can order now. If you enjoyed our conversation, please subscribe, leave a review and share it with a friend. This podcast has been sponsored by the Ethics and Public Policy Center. You can learn more about our work at our website, eppc.org, including our Life and Family Initiative.