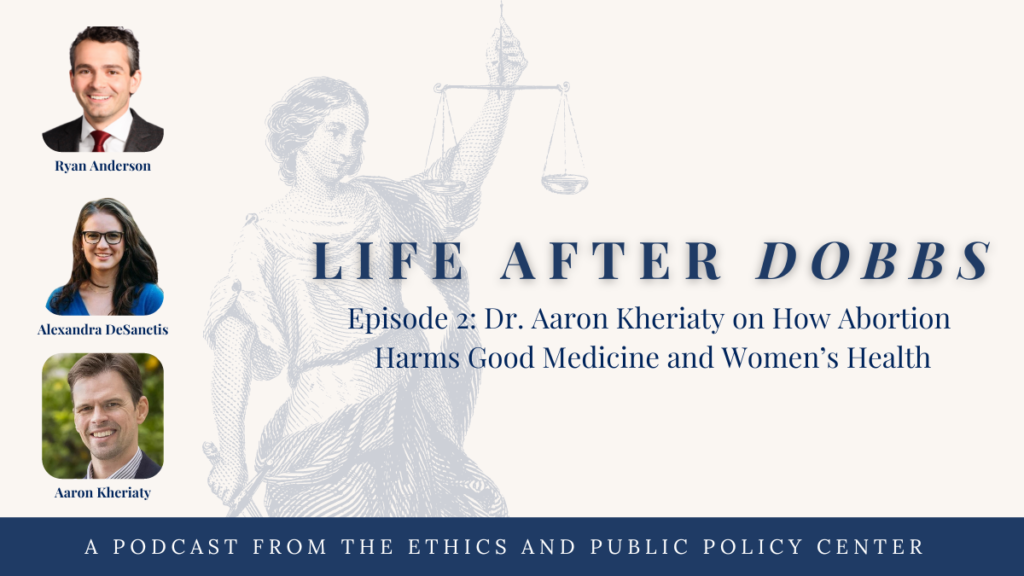

In the second episode of EPPC’s Life After Dobbs podcast, hosts Ryan T. Anderson and Alexandra DeSanctis talk with Dr. Aaron Kheriaty about when human life begins and how we define personhood, the profound moral and bioethical questions surrounding abortion, and why abortion is so harmful not only to the unborn but to women and to the doctors who are involved.

Listen on:

Show Notes

Guest

Follow Aaron on Twitter: @akheriaty

Click here to learn more about EPPC’s Program on Bioethics and American Democracy.

—

Hosts

Ryan T. Anderson (@RyanTAnd)

Alexandra DeSanctis (@xan_desanctis)

Order Ryan and Xan’s new book Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing today!

Click here to learn more about EPPC’s Life and Family Initiative.

—

Life After Dobbs is a production of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. For more information, follow us on Twitter (@EPPCdc) or visit our website at eppc.org.

Produced by Josh Britton and Mark Shanoudy

Edited by Sarah Schutte

Art by Ella Sullivan Ramsay

with additional support by Christopher McCaffery and Alex Gorman

Episode Transcript

Ryan T. Anderson:

I’m Ryan Anderson, and welcome again to Life After Dobbs, our podcast series that asks big questions about abortion and the future of the pro-life movement.

My co-host Alexandra DeSanctis and I are joined in this episode by Dr. Aaron Kheriaty, and we’re excited to do a deep-dive with him on some of the profound moral and bioethical questions surrounding abortion.

Dr. Kheriaty is a fellow at EPPC, where he directs our program in Bioethics and American Democracy. For many years, he was professor of psychiatry at the University of California Irvine School of Medicine and director of the Medical Ethics program at UCI Health, where he chaired the ethics committee. Dr. Kheriaty studied philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, and he earned his medical degree from Georgetown University.

With his medical and ethical expertise, Dr. Kheriaty is the perfect guest to help us walk through questions about when human life begins and how we define personhood, as well as some of the ethical issues surrounding pregnancy complications.

Just a heads-up that this conversation discusses pregnancy and abortion in medical detail in a few places. We trust that by examining these matters in detail, we can better understand just why abortion is so harmful not only to the unborn but to women and to the doctors who are involved.

And now, Alexandra will kick off our interview with Dr. Aaron Kheriaty.

Alexandra Desanctis:

All right, thank you so much for joining us today, Aaron. I want to start out, I know you’re a doctor, so you’re a great person to speak to this first question. Ryan and I would love to know: is abortion ever medically necessary?

Aaron Kheriaty:

The answer is simple and straightforward. The answer is clearly no. So the situations in which a mother’s life or health may be at risk from a pregnancy occur typically later in the pregnancy, when we’ve gotten to the point where induction of labor is medically feasible, so we can deliver the child early, if need be, in order to interrupt the pregnancy in a case where a woman has, let’s say, severe preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome. And that may introduce some additional risks to the newborn, to the neonate, but neonatal care, as I think most people are aware, has made enormous strides in the last couple of decades and the age at which a baby can survive outside the womb keeps getting pushed back further and further in pregnancies. So for a while conventional wisdom was 24 weeks was the cutoff for what we call viability, or the ability of the fetus to survive outside the womb if the baby is delivered, but that has been pushed back in some cases to 22 weeks which is really sort of extraordinary.

So there have been debates about this in the courts. But it’s clear now, and the court has more or less accepted the medical evidence on this, that there’s really no situation in which it would be safer for the mother to have a late-term abortion versus an emergency C-section or induction of labor to deliver the baby. So, abortion advocates have tried really hard to find rare circumstances or unusual medical or pregnancy-related conditions where they could plausibly make the case that well, here’s a situation in which if we deliver the baby, instead of doing an abortion, that’s going to somehow elevate the medical risks to the mother. And they basically haven’t been able to come up with a situation like that. So that’s a long-winded answer to a very simple question, but the simple answer to the question of whether abortion is ever medically necessary is that no, it’s not, there’s always an alternative that does not involve the direct killing of the fetus.

Alexandra Desanctis:

Yeah. And I appreciate the distinction you raised there, which is if there were a case where there was some sort of health risk to the mother she could simply give birth. Right. And what we’re talking about in abortion is a procedure where we’re not ending pregnancy, right? They call it terminating pregnancy, but what they’re actually doing is directly killing the unborn child. And this is a particularly important distinction because this claim that abortion can be necessary in health emergencies for the mother, or if there’s, there’s a kind of disability diagnosis for the unborn child or something like that these are the justifications we often hear for abortion later in pregnancy. The idea being women are going to die, essentially, if they can’t get abortions, but as you say, there’s no reason they can’t simply give birth. And in fact, they will most likely be safer if they do so. And so abortion is actually not a solution in those cases.

Aaron Kheriaty:

That’s correct.

Ryan T. Anderson:

And one of the things that both of you just hit on, you both used the phrase direct killing when describing what an abortion is. And one of the things that Alexandria and I do in our book is point out that there are certain situations where what might be known as an indirect abortion, or non-intentional killing might be medically required. And so Aaron, I wonder, both as a physician and as a bioethics expert, could you talk about what about the case of ectopic pregnancy or what about the case of uterine cancer? A lot of what we saw in the days after the leaked Dobbs opinion, were people saying that this would mean no medical care in the case of ectopic pregnancy or no medical care in the case of uterine cancer. I even saw some people making the ludicrous claim that it would mean no medical care after a miscarriage to make sure that all the body parts were delivered. So could you help listeners understand the bioethical distinctions, the medical distinctions, between intended and unintended and what’s going on in medical treatments for things like ectopic pregnancy or uterine cancer.

Aaron Kheriaty:

Yeah. Thanks, Ryan. This is a really important question. And clearly what you’re describing in terms of abortion advocates saying that people are not going to get care for ectopic pregnancies, or they’re not going to be able to get what’s called a dilation and evacuation after a miscarriage where the fetal remains of an unborn child that’s already dead are removed from the uterus. That, that is of course, nonsense. It’s merely propaganda to try to scare people. So let’s talk about ectopic pregnancy. I think this is a helpful example. So an ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy in which the fertilized ovum, the embryo in its earliest stage of development, instead of implanting in the uterus where normal pregnancy occurs implants in the fallopian tube. The fallopian tube is the structure that connects the ovary, which releases the egg to the uterus, and actually fertilization normally takes place in the fallopian tube.

And then it takes about three days for the embryo to traverse the fallopian tube and implant in the uterus. But in some cases, instead of doing that, the embryo will implant in the fallopian tube and this results in a situation that is incompatible with the life and development of the unborn child, because the fallopian tube is not a structure that can house a pregnancy. And in fact, if this situation continues for long, it can become medically dangerous for the mother because as the embryo grows into the blastocyst and the subsequent stages of early development, it’s getting bigger and bigger, and it’s inside a very small structure that doesn’t have room for it. And what can happen in these situations is that the fallopian tube can rupture, and very often these resolve spontaneously and the embryo dies and nothing untoward happens, but in situations in which the embryo continues to grow, eventually the fallopian tube can rupture.

And that can cause bleeding in a pretty emergent situation for the mother. So when ectopic topic pregnancies are discovered and diagnosed they need to be medically dealt with, and there’s a procedure called the salpingectomy, which is basically a surgical procedure to to remove the fallopian tube, which has the foreseeable, though not necessarily intended, consequence of indirectly killing the the early human life, the embryo inside the fallopian tube, but as when we remove a cancer in the uterus and other situations that are analogous, the so-called principle of double effect applies here. And this is where we get into the ethics of killing directly, which I mentioned earlier, which is what abortion does, versus doing a medical procedure in which a foreseeable though not necessarily intended consequence happens that if we could avoid it, we would avoid it, but this is a situation which we perhaps can’t avoid it.

So it’s perfectly ethically legitimate, according to most moral systems. For example, Catholic moral theology would allow for the salpingectomy in order to prevent the ectopic rupture in the case of an ectopic pregnancy, even knowing that the embryo was going to die as an indirect consequence of that procedure. So all of those things, of course, under the law would still be permissible. Women would still be able to get whatever care they needed for ectopic pregnancies or uterine cancer, of course for miscarriage, which does not involve abortion. So, even though the name of the procedure is the same in the case of a miscarriage, and this can get somewhat confusing for women who don’t understand the distinction, but a dilation and extraction of a live fetus is of course an abortion whereas a dilation and extraction, or as it’s known in an earlier stage of pregnancy, a dilation and curettage procedure, of a miscarriage where the unborn child has already died is of course not an abortion, even though this same medical term is used to describe both procedures.

Alexandra Desanctis:

That’s really helpful. And, I think this kind of medical clarity is just totally absent from so many of our conversations about abortion because abortion supporters like it that way, right? The first thing they want to talk about when abortion comes up is not “I think abortion is great and should be legal throughout all nine months of pregnancy.” They wanna talk about how women with ectopic pregnancies are going to die, or women who had a miscarriage are gonna be thrown in jail because people claim it was the same as an abortion, or just these crazy cases that if we bring medical clarity and facts to it are just obviously not true, right? It’s really a distraction. And it’s very important to understand the medical details here.

Ryan T. Anderson:

And you saw that also in the days after the leaked Dobbs opinion most people didn’t want talk about the actual justification of Roe or Casey, or what an abortion is. They wanted to talk about…President Biden said this will lead to the segregation of LGBT identified students at school, or this will mean they’re going to outlaw contraception–it’s as if they want to talk about everything other than abortion. And I think that tells you something about what they themselves know about the public opinion on this, that when a good pro-life argument is made, it resonates with people and the American people are not on the side of abortion. And so Aaron, that clarity you brought was really helpful in thinking through some of the tougher medical cases.

Alexandra Desanctis:

Yeah. Another question we’re hoping you could clarify for us, especially I think with Roe v. Wade kind of on the chopping block here and discussions about the decision on the table. Something pro-lifers bring up a lot is medicine, science, technology surrounding pregnancy–all of this has evolved and developed quite a bit since the time that Roe was decided. And we now know quite a bit more in particular about what’s going on in the womb during pregnancy and more about unborn human life. What do medicine and science have to tell us about the question of when human life begins?

Aaron Kheriaty:

Well, the answer to that question is quite clear. In fact, you can find it in any embryology textbook. A new human life or a whole human organism comes into being at the moment of fertilization or what we sometimes refer to as the moment of conception, the meeting of the sperm and egg to form what scientists call the zygote, or the single-cell human organism, that then grows into a blastocyst, which is slightly larger, which then grows into an embryo, which then grows into a fetus. All of these terms that I’m using, these medical terms are nothing more than a description of a particular stage of human development. They’re not a description of a different kind of organism or a different kind of being. So, calling something an embryo or a fetus, those words function in a way that’s analogous to calling a human being a child, or an adolescent, or an adult.

These terms all describe the same human being and the same human organism. But they just simply describe a different stage of development. And so when human life begins is a question that’s been clearly answered scientifically, it begins at the moment of conception. What the law to permit abortion has done to try to do an end run around that scientific fact is to attempt to distinguish between a human life or a human being, or a human organism and a human person, and this idea of person being a legal construct to designate a human being who has human rights and who is protected under law. But the problem with trying to drive a wedge between a human being and a human person is that the criteria for what counts as a human person is always going to be arbitrary.

It’s going to be decided by people in power and a certain class of human beings is going to be excluded and discriminated against and mistreated. So the moment we start trying to say that there are certain human beings that either due to their stage of development or due to their status of still being in the womb or due to their skin color or their level of disability or their age, or their illness, or any other criteria where that certain class of human beings is no longer protected under the law, we are headed down the road of tyranny. We’re headed down the road of killing innocent human beings. Every time in human history that a regime has attempted to do this, it’s ended in some form of disaster, some sort of terrible tragedy that resulted in a certain group of human beings being harmed or liquidated or simply killed because they didn’t have the characteristics that the ruling class saw as worthy of protection or worthy of inclusion in the human family and abortion is no different in that regard.

I think it’s very important to understand that the question of when human life begins has been clearly answered by science and this arbitrary distinction between a human being and a human person is a legal construct that in the past and in the present continues to lead to very, very bad outcomes.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Yeah, when Alexandra and I were drafting–it’s the very first chapter of the book that we discuss the harms to the unborn child. And when we get to what are the justifications that the pro abortion side makes, and we get to all the personhood arguments, and we have to explain to readers the Peter Singer-style personhood and the Michael Tooley and the Mary Anne Warren. And it’s just striking how unpersuasive those arguments are and everything you just said…the whole history of when we’ve denied personhood to a certain segment of the population it’s always been might makes right. And it never has ended well for those who were in power. And I think that’s why you see so many people at the popular level try to say it’s just a clump of cells or science doesn’t know when life begins. The actual science is just, as you said, crystal clear, and yet the philosophy of personhood is so draconian and it’s so mistaken that I think that’s why people would instead want to debate the issue on the biological grounds.

Aaron Kheriaty:

Yeah. Yeah. Any criteria that abortion advocates have proposed to try to capture unborn human life under the category of non personhood does one of two things: either it doesn’t actually apply to unborn human life, or it does too much work. And the criteria has something to do with, let’s say, the the ability to autonomously direct one’s own life choices, which of course applies not just to unborn human life but to newborn human beings, to elderly individuals with dementia, and to deal with that issue, some advocates of abortion actually follow that logic to its logical conclusion and end up making public arguments in favor of infanticide or in favor of euthanasia. And as horrifying as that is, we could say, well at least they’re being logically consistent and they’re following their premises out to their logical conclusion.

It becomes a kind of what philosophers call a reductio ad absurdum: follow your premises out to the logical conclusion. And if they result in an absurd result that nobody would accept that suggests that maybe your premises are wrong. But more often than not, people don’t want to say the quiet part out loud. So they go on just muddying the waters. And that’s I think the kind of propaganda that you described at the beginning of this podcast. The fog of grossly inaccurate information and the cloud of just nonsense that is thrown up when you start talking publicly about abortion functions to get people not to think rigorously, or logically, or clearly, because that’s probably proven to be the most effective means for advocates of abortion to avoid having these arguments, because once you start having these arguments the pro-life position starts looking clearly like the most logical way to go.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Yeah, that’s exactly right. And you think about–the 1972 journal article by the academic philosopher, Michael Tooley was titled ‘Abortion and Infanticide.’ And there’s some academics like Tooley, like Peter Singer, that are willing to bite the bullet and have that logical consistency, but it’s never been persuasive or acceptable to the American people, which is why the political pro-abort movement really has to muddy the water. But let me change gears real quick, because we’ve asked you about abortion ever being medically necessary and then the science of when a human being exists. For our listeners who don’t know, your expertise is in psychiatry. You’re a practicing psychiatrist, you’ve taught psychiatry at the university medical school level. One of the arguments that we see abortion advocates make is that women need abortion for their mental health. And then one of the counterarguments we see pro-lifers make, and we cover this in the book as well, is that actually abortion has negative consequences, mental health consequences for women, and this is particularly the case with chemical self-administered abortion. Could you share with listeners your insights into that aspect of the debate?

Aaron Kheriaty:

Sure. This is a really important issue and I’ve I’ve dug into the research on this very extensively and written about it fairly extensively in some expert witness declarations that I’ve submitted to the court, including actually on the Dobbs case, on a different aspect of the Dobbs case that was being litigated at the district court and the circuit court level, but long story short: lots of research has been done on mental health consequences of abortion. And the research suggests overall on balance–and again, at the individual level of this case versus that case, there are always exceptions, but overall on balance, abortion tends to harm or detract from women’s mental health. So we see elevated rates of depression, of anxiety disorders, of suicidal thinking and suicidal behavior.

Very clearly we see elevated rates of substance use disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, and disorders that are sort of trauma-related, PTSD-type problems. When you compare women who have had an abortion versus women who carry their pregnancies to term, there’s ongoing debate about the details of these findings, but I think the overall trends are very clear and at this point difficult to refute those outcomes. So what we know from the research literature is that abortion tends to carry consequences for women’s mental health that overall is harmful to women. And it’s important when you look at that research to make sure that you’re looking at studies that follow women sufficiently long-term, because one of the things that happens very often with abortion is that in the weeks or months immediately following the abortion, many women report a sense of relief or a sense that their stress has been reduced by going through that procedure, which is understandable.

You can imagine a woman in a crisis pregnancy situation trying to imagine how having a baby might upend her life or negatively impact her financially and all the social, economic, familial reasons that tend to incline or push some women in the direction of abortion. Those are very real concerns and they weigh heavily on a woman facing an unintended or unwanted pregnancy, particularly a woman who does not have sufficient support from the father of the child or from her family or from her social network. And so abortion seems like a ready-made, quick, easy and many women are promised it’s going to be painless, solution to that conundrum, to that difficult life circumstance. And so, if you look at women’s mental health kind of immediately after abortion, many women report that their level of anxiety diminishes, for example, but what tends to happen is if you follow them out long-term, you see that the wounds or the scars from abortion may not manifest immediately, but they tend to plague women down the road.

So many women, for example, report that the the trauma or the unresolved grief from the abortion does not resurface until they get pregnant again which may be many years down the road, or perhaps it resurfaces when later down the road they’re married and wanting to have children and are dealing with fertility problems. And at that point they are thinking back to a time when they were able to conceive and when they were pregnant and chose to end that pregnancy through abortion. And and now they’re in a situation in which they’re hoping to have children and struggling with that. That can be another moment when a woman starts to manifest the trauma or the depression or the anxiety, or maybe turns to drugs and alcohol to deal with the sort of long-term consequences of having made that decision to end the life of her unborn child.

So the issues surrounding mental health and abortion are complex, but certainly if you look at the big picture and you look over a sufficient span of time, you see that the problems don’t always manifest immediately. But eventually at least for many women, we’re left with a woman who has been wounded and scarred by having gone through an abortion, she’s dealing with the additional anguish of having her pain stigmatized or sort of not publicly recognized. Unlike a woman who maybe has a miscarriage who could disclose that at least to close family or friends who would be sympathetic and understanding even if she doesn’t want it to be widely known publicly that she lost a pregnancy. In contrast to that kind of situation, a woman who has had an abortion may be dealing with complicated feelings of guilt and shame, regret, and feel like I have no one that I can talk to about this pain.

So the anguish is compounded by the fact that the grief remains hidden and unspoken, and so women are oftentimes suffering with those sorts of feelings alone. It’s interesting–I’ve seen many women who decades after their abortion still have unresolved grief. That’s right there beneath the surface, if you ask about it, but they’ve they’ve never disclosed their abortion to anyone. And they’ve never talked about what it was like to go through that. So women in their fifth or sixth decade of life who for the first time in the context of a psychiatric evaluation–maybe when they’re in the emergency room with suicidal thinking, or they come see me in a clinic to deal with depression or some other mental health issue–when we get to their pregnancy history and I inquire about the abortion, immediately when we touch on that issue the tears come and the grief is right there, present in the room, even if the abortion may have taken place 30 or 40 years ago. This is actually the first time that maybe that this woman has actually spoken about that to anyone or disclosed to anyone what had happened or what it was like for her to go through that. So these are not wounds that time automatically heals and many women sadly sort of carry that burden alone sometimes for decades. And that could have profoundly negative consequences on her life.

Alexandra Desanctis:

Yeah. I really appreciate all the kind of data you bring to bear on that, because I think something we talk about quite a bit in the book is how when it comes to women and the abortion rights movement, the language we often hear about abortion, we don’t hear abortion supporters say it’s great to kill unborn children, right? The argument is women need this, or women are better off because of abortions and kind of to tie into what you were mentioning about the guilt and shame and stigma that’s sort of kept to themselves oftentimes. If women are struggling with these feelings after having had an abortion, I think a lot of that comes from sort of the language of the pro-abortion folks who want to say “abortion is always a great solution. And if women do experience regret or sadness afterwards, it’s because of pro-lifers who are shaming them,” right? As opposed to, “maybe it’s because we, as abortion supporters deny that women might ever be sad afterwards for real, or might actually suffer at all from abortion.” And so they really minimize the idea that there are any harms, let alone mental health harms to abortion. So we talk quite a bit about that in the book, both kind of the psychological after-effects and harms that women suffer, the physical after-effects. And so I was hoping we could touch on a similar theme. I know, according to estimates, chemical abortions are on the rise. They account for more than half of abortions. These are early in pregnancy, usually around 10 weeks or before that, 12 weeks.

So, I’m wondering if you could touch on, specifically, if there are more negative effects that women experience psychologically, certainly physically, from chemical abortion, because in the case of an abortion pill, a woman receives it from a doctor sometimes now, even via telemedicine, without seeing a doctor in-person, takes it at home and undergoes the kind of induced early miscarriage symptoms at home by herself. And so if you could talk a bit about both the implications of chemical abortion being on the rise, but specifically the mental health implications of that for women.

Aaron Kheriaty:

Right. That’s a really important question. I think abortion advocates see chemical abortion is a direction that they want to move things in because it doesn’t require that a woman go into a clinic, doesn’t require a woman to have to undergo a procedure where she is literally up in stirrups and put under at least mild sedation and a doctor is required to do the surgical abortion. So, the push for chemical abortion is a push in the direction of ease and efficiency. And I think some people even have made the case that this is going to be less stressful, less potentially traumatic or difficult, for the woman undergoing abortion. But in fact, what we’ve seen from some early case reports, and I think there is a need for more robust research to confirm this, but certainly the early reports from women that have undergone chemical abortions, or maybe have a history of having undergone both a surgical and a chemical abortion, a surgical abortion in a clinic and a chemical abortion at home, is that the latter actually in some ways is more traumatic, more potentially anguishing, and can lead to an increased burden of a kind of complicated grief that’s overladen with guilt and shame.

And the reason is this. So…there’s a couple of reasons. So, listeners will forgive me for getting a little bit explicit about what actually happens in a chemical abortion, but I think this is necessary to really understand the reality of what we’re talking about. So a chemical abortion is not just taking a few pills at home, going to bed, and waking up the next morning not being pregnant anymore. What actually happens is that these pills first of all kill the fetus and then second of all expel the unborn child from the uterus. And that whole process happens at home. So a woman ends up in the bathtub or on the toilet when the placenta and the uterine and the sac and the fetus is expelled.

Very often, the fetus is at a sufficient stage of development that the human form of the fetus can be viewed with the naked eye and the woman then has to dispose of the baby herself, usually by flushing it down the toilet. So unlike going into a clinic and being under some form of sedation where yes, she is getting a procedure, but she doesn’t necessarily see her unborn child, in this case, in the case of an abortion, she sees a bloody sac or in some cases, even those ‘products of conception’ that include a visible human form that’s clearly able to be seen. That brings home to many women the reality of what exactly is happening and the reality of what unborn life in the womb actually is and looks like and makes it harder to dissociate from that and to keep it out of sight, out of mind.

And the other complicating factor is that when a woman goes into a clinic and lays down on the table and allows a physician to do the procedure, that can put some psychological distance between her and the procedure in the sense that someone else is doing this thing to me or someone else is doing this thing to my baby. And I think that can help diminish maybe some sense of responsibility for what is happening, whereas with a chemical abortion at home, the woman is actually ingesting the pills that produce the expulsion of the unborn child. And I think just psychologically that brings home the sense of my own moral agency actually affecting the death of the baby and actually producing the abortion. So it’s sort of the psychological difference between maybe someone who gives the order to a soldier to pull the trigger versus the soldier who pulls the trigger and actually witnesses the consequences of that action.

And you could say morally those two are the same. In both cases, the person is responsible because they’re consenting for it, which is true. But psychologically, there is a sense in which the chemical abortion at home introduces new psychological burdens to a woman who is very up close and personal and in a sense a firsthand witness to the process rather than being in a state of mind where she is a little bit more psychologically detached from what’s going on in the abortion. And so as a consequence of that, many women report that the chemical abortion was actually more traumatic and it led to more complicated forms of guilt and grief or regret or shame than the surgical abortions.

Alexandra Desanctis:

Yeah. I really appreciate that helpful explanation because I think women are often told, or kind of chemical abortion is billed as this sort of easy solution that you take before you even really have felt like you’re pregnant, right? You’re not showing at all. And Planned Parenthood advertises chemical abortions as “it’ll just be like a heavy period.” And that’s just not the experience that a lot of people have. And so I think it’s important for women to know this is not just kind of like a nice magic pill and you wake up and everything’s fine. It’s actually a lot more devastating than that.

Aaron Kheriaty:

Yeah. And actually, unlike just a heavy period, many women report that the process is very painful. It involves a lot more bleeding than they anticipated…this sort of heavy vaginal bleeding would be distressing for any woman–whether or not she was she was aware that she was pregnant. So, I hate to drill down so much on some of the more explicit medical details, but part of the process of informed consent from an ethical standpoint is that women be adequately informed of exactly what to expect. And I think many women who undergo chemical abortions feel a sense of betrayal that what the process was gonna look and feel and be like was was minimized. And they were not really told the truth. And when they go through the experience, they feel a sense of betrayal or like they were they were sold something that was not at all like what the actual experience turned out to be.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Aaron, this is really helpful. And I find this personally impactful in terms of what abortion does to the person who performs it and whether that’s a woman who self-administers through an abortion pill, and that led my mind to question, what does it mean for the medical doctor who performs abortion, Xan and I, we have a chapter in the book about how abortion has really corrupted the medical profession. And we cover that in a variety of ways. One is how it turned professional medical associations into just like nakedly partisan lobbyist groups on behalf of abortion. But I also wonder what this means at the level of the physician him or herself who specializes in killing unborn babies. Could you speak to both about how abortion has corrupted your profession?

Aaron Kheriaty:

So the, the purpose and the ends of medicine since Hippocratic times have been the health and healing of the sick patient who comes to us for care, the vulnerable patient, who because of their illness needs to entrust themselves to the physician because the vulnerable patient may not have the knowledge or skills necessary to affect their own healing. So trust is essential to the doctor-patient relationship. And the physician from ancient times has always been tempted to use his or her knowledge and skills for things other than health and healing. And starting with the Hippocratic oath, Western medicine was founded on the public promise–an oath is a solemnly sworn public promise–to use one’s knowledge and skills only for the purpose of health and healing. The Hippocratic oath is of course a pre-Christian document from the third century BC wherein physicians promise not to do abortions and promise not to euthanize patients even if a patient asks for a deadly drug.

So, Western medicine was founded on the promise to maintain the patient’s and the public’s trust by always using my knowledge and skills only for the purpose of health and healing. And that’s been reaffirmed up until modern medicine started embracing abortion. And in most cases that still is reaffirmed by our professional medical associations. So the American Medical Association, their code of ethics still maintains that physicians should not participate in euthanasia and assisted suicide, still maintains that physicians should not use their knowledge of physiology or pharmacology to participate in capital punishment to participate in lethal injections, even when that’s authorized by the state. The AMA doesn’t take a political or moral position on capital punishment itself. It says you’re free to believe and vote however you like on capital punishment as a member of our professional medical association, but as a physician, there’s an ethic internal to medicine that says you cannot as a physician use your knowledge and skills for the purpose of killing, even if that state-sponsored or state-sanctioned execution might be legally justified. Unfortunately when it comes to abortion, modern medicine lost its bearings and it abandoned this basic orientation, and that can’t help but have a corrosive effect, not just on prenatal care or on obstetrics, but on other areas of medicine as well. Because again, we’re free to choose our premises, but inexorably over time, we’re gonna be pushed in the direction of following those premises out to their logical conclusion. And so what happens when you introduce that exception to the general rule, that in the case of unborn human life, doctors can use their knowledge and skills for the purpose of killing rather than the purpose of healing, that’s going to start to have a corrosive effect on the ethics of medicine as a whole.

And so we see now the push, for example, to allow doctors to use their knowledge and skills for the purpose of killing at the end of life. And I think the assisted suicide and euthanasia push that we’ve seen over the last couple of decades is a logical outgrowth of the acceptance of abortion in medicine. So, we compromise those principles at the beginning of life. And now, many states, certainly my home state of California, have embraced the idea that we could do that at the end of life as well by permitting doctors, at the end of life, to prescribe a deadly drug for patients that request it. And so I think there is certainly a tight logical connection, but also there’s a kind of institutional connection between abortion and euthanasia and assisted suicide in medicine. And I think unless medicine can reorient and find its bearings and ground itself, again, in that great Hippocratic tradition that would say doctors should promise, and should adhere to the principle that their role is health and healing and not killing, unless we could do that with abortion, we’re going to continue experiencing the corrosive effects of that in other areas of medicine, particularly at the end of life.

Alexandra Desanctis:

Yeah, I think that’s really essential context and a good point to wrap up our conversation on. We have a whole chapter in our book about medicine and, in particular, how abortion is pitched as healthcare. One of the primary arguments in favor of abortion is this is just women’s healthcare, right? This is nothing more than getting a tooth pulled or something like that and you’re kind of healing. And of course, killing is not a form of healthcare. And we can see similar to early in our conversation, we were talking about personhood, how the logic of depersonifying or dehumanizing one vulnerable group of human beings naturally leads to doing the same to other categories. And it’s not a society that any of us want to live in. So we’d love to thank you, Aaron, for joining us today. It’s been a great conversation.

Aaron Kheriaty:

Likewise, thank you, Alexandra and Ryan. I enjoyed the conversation very much.