Published June 12, 2015

The announcement by James H. Billington that he will retire from his post as Librarian of Congress, effective January 1, marks the beginning of the end of an extraordinarily distinguished career of public service and sets a very high bar of expectation for his successor. For despite the carping from the peanut galleries in recent months, Jim Billington will certainly be remembered as one of the great custodians of one of the world’s great cultural treasures — and perhaps the greatest.

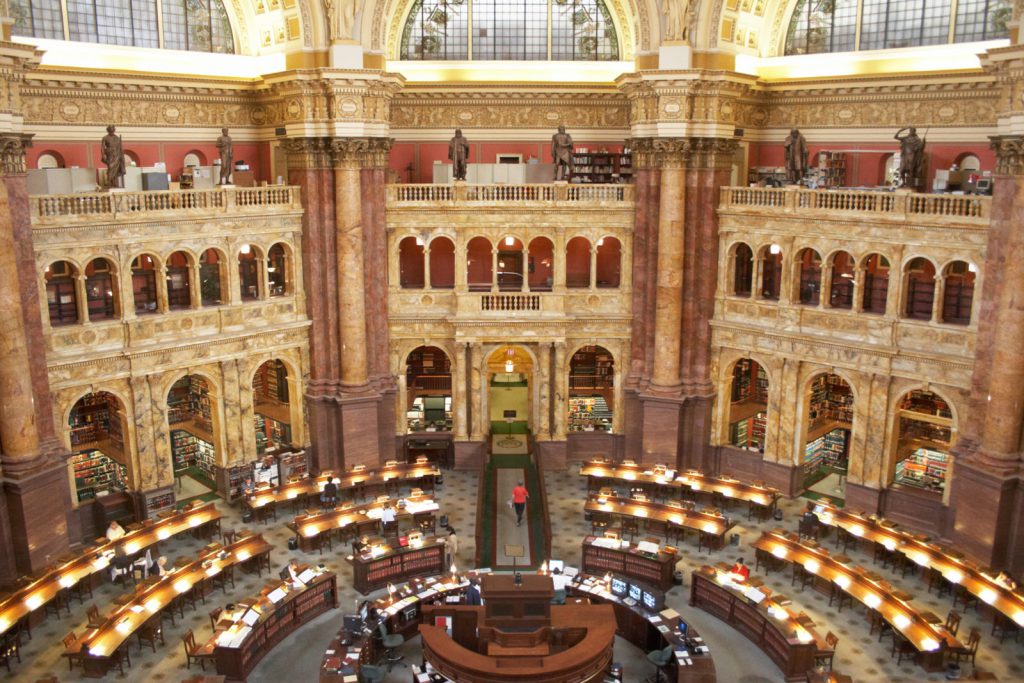

In almost three decades of service, Jim Billington grew the Library of Congress in unprecedented ways. He pushed it into the digital age by raising half a billion dollars in private funds. He co-founded the National Book Festival with Laura Bush, drawing millions of Americans every year into a celebration of reading. He presided over the renovation of the magnificent Jefferson Building. He founded the Kluge Center for scholars at the Library and established the Kluge Prize for lifetime achievement in the study of humanity — a worthy complement to the Nobel prizes and a needed alternative to the political correctness that now dominates the Nobel literature prize. He created the Gershwin Prize to honor lifetime achievement in popular songwriting and he built the Packard Center for Film Preservation to safeguard another facet of American popular culture. At the same time, he was the intellectual driving force behind a number of groundbreaking exhibits that, through the books created from them, continue to enrich the nation’s high-cultural life — and challenge many of the shibboleths of the contemporary academy, especially in matters of religion and modernity.

Perhaps most impressively, Billington not only protected this great national and global resource from the political tong wars of the Potomac littoral; he made the Library of Congress one of the last refuges in Washington of serious bipartisanship and calm, considered conversation. It was a skill he had displayed in his previous job as director of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and I think its refinement over time was ultimately based on the fact that James Hadley Billington is a brilliant teacher and an old-school Christian gentleman. In the year I spent at the Wilson Center, surrounded by a very diverse group of fellow fellows, I would watch in admiration as, time after time, Jim Billington would come into a circle of conversation, listen carefully, and then ask the one question that got everyone thinking different thoughts and actually engaging others’ thoughts, rather than recycling previously held opinions. At the LOC, Billington worked that same magic with politicians as well as with scholars. And as both of those tribes, the solons and the scribes, are not best known for the humility that makes fresh thinking possible, it now strikes me that it was Billington’s innate courtesy, as well as his scintillating intellect, that made it possible for him to get others to think things through again, and in a fresh way.

All of this creates a challenging and impressive legacy on which his successor, who will be nominated by the president and must be confirmed by the Senate, ought to build.

It’s a good thing that the United States hasn’t got the equivalent of a European ministry of culture: In the American understanding of things, the culture is the primary responsibility of the free associations of civil society, not the state. Yet there is an obvious common border, perhaps better described as a membrane, between the culture and the state. Ideas really do have consequences, and that is as true of governance as it is of every other form of human activity. So the health of both high culture and popular culture affects the life of the polis in ways the polis may not always recognize.

Yet despite the fact that the U.S. doesn’t have a ministry of culture, it does have one of the world’s greatest cultural centers, in the Library of Congress — which means that the Librarian of Congress can, if he or she chooses, play an informal role as a de facto, if not de jure, minister of culture. The Librarian can, in addition to safeguarding the treasures housed in the world’s greatest assembly of human knowledge and making those materials as widely available as possible, set a cultural tone for Washington and, ultimately, for the country.

James H. Billington did precisely that: In a variety of ways, he called the best out of American high culture and popular culture. That he did so at a time when pop culture was becoming increasingly tawdry and high culture was threatened with grave incoherence only underscores his achievement — as it helps define the qualities necessary in his successor.

In the immediate aftermath of Billington’s announcement that he would retire at the beginning of next year, there was a flurry of chatter about what the Library of Congress needed: stronger management, better integration into the digital world, greater accessibility to the public, whatever. Those are all important issues (and it is nothing short of calumny to suggest that Jim Billington didn’t work hard to address them). But the far more crucial criteria for the next Librarian of Congress involve character and vision.

It would be a global, not just national tragedy if the Library of Congress became another citadel of academic political correctness, or became caught up in partisanship, or became otherwise politicized. The president bears a grave responsibility for ensuring that that does not happen, by choosing a new nominee (who might well serve for decades) by criteria far more serious than immediate political expediency. If that responsibility is not met, then the U.S. Senate has the responsibility to reject an unqualified, partisan, or politically correct nominee, tell the White House to try again, and help the administration find the kind of person the nation, and the world, deserve at the helm of the Library of Congress.

The greatest library of the ancient world, the Library of Alexandria., was destroyed over time by fire and war. But there are many ways to destroy a great center of human learning, some of them far more subtle than fire and sword. At a time of cultural fragmentation and the nasty politicization of moral and cultural differences, the Librarian of Congress can and should be someone who takes care that what happened in ancient Alexandria does not happen in 21st-century Washington, because of those more subtle, but nonetheless insidious, solvents. Finding that person means more than looking at “skill sets”; it means pondering character and vision.

And that means finding a new Librarian of Congress who will build on, not dismantle, the character, vision, and legacy of James H. Billington.

— George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies.